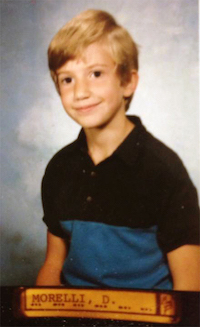

Dante Morelli

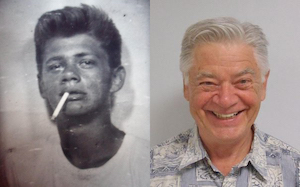

I vividly remember Christmas morning, 1986. My older brother Jason and I tore down the stairs in our pajamas to see what presents awaited us. I will never forget the moment when my brother ripped the wrapping paper off a long box. He was over the moon to see the Nintendo console that made its entrance into our world. It wasn’t until years later that I realized the Nintendo didn’t magically arrive on its own. It arrived there through the collaboration of a number of people. My mother often struggled to make ends meet while working as a nurse and attending school to earn her RN. The Christmas gifts under our tree were the result of her hard work as a single mother along with the support from her father, and my father, so that we could enjoy that incredible day. Nothing ever simply “happens.” In fact, our own biographies are laden with the efforts and collaboration of others for which we cannot take full credit. Our union is no different. Our identity today, and where we stand contractually, is not the work of any singular person. Instead, it’s a culmination of many people who helped lay a foundation of union activism. This look into our history became present to me when I attend Professor Ed Eriksson’s retirement party in April 2019. For those who do not know, Professor Eriksson is a larger than life personality. He tells stories with the enthusiasm and suspense as if you are one of the characters present in the conflict of the narrative. Through his cadence, facial expressions and gestures, the story is alive for everyone in the audience to experience and embody. At his retirement party, he told the following story about the creation of our union. It was beautiful and enriching, especially for me as I hoped to be elected the next president of the FA. In my mid-to-late 20s, I had more energy than I knew what to do with. We had different schedules then and no contract and we had to stay on campus for more than our present office hours. So between classes I started walking around and making friends with any teachers I’d run into, and in those days there were over four hundred full-time faculty. I met them all. I would wander around the campus buildings, stop in at faculty offices, sit down, and shoot the breeze. This vagabond impulse soon assumed a political objective, and that was to convince the other teachers to consider organizing—forming a union. The impetus to this was the sudden, high-handed firing of a theater director by the then President Ammerman, in the middle of the 1968 fall semester. I was close to the theater at the time, being the house manager, as well as an English teacher, and knowing the unfortunate person and being familiar with the situation. And it dawned on me that this could happen to me and to anybody else employed by the college.

What could I do if I were fired? Given my employment history, it wouldn’t have come as a surprise. If this happened, I had one other option, so I believed, and that was to go off to the big city and become an actor. One part of me saw this as a fairly desirable option; the other part of me, the one with a wife and a two-year-old son, told me to take it as it came and to continue talking, only this time seriously, to the other teachers around the campus. See what might develop. Meanwhile, collect my salary and pay the rent for a small cottage in Farmingville. That’s when the real excitement began. Of the four hundred or so faculty, practically half at first saw me as an uncontrolled lunatic, reckless, foolish, and about to create a chaotic situation that would certainly destroy the college: the institution, perched on the hill in Selden, was only five years old. In which case we’d all be out of work. Moreover, since when, so the reasoning went among them, since when did college teachers join unions? We were professionals. Like lawyers, doctors, and dentists. They didn’t form unions. They didn’t negotiate salaries and privileges. They earned them. We didn’t have much in the way of salaries and privileges or protections, but what did we expect? We didn’t create our own jobs; we were given them—and damned lucky to have them. Fortunately, among the other half, we had the English department, with fifty-five full-time teachers, Steve Klipstein among them, who understood the situation with a shrewder sense of reality. This was interesting, since historically it was the social science people who tended to lead the faculty in other colleges—but not here. We had scattered support from math and science; a little from business; some from phys ed and nursing, the library, and the rest of the liberal arts, one from mechanical technology. And among all these, a lot of fence-sitters and a lot of arguing and shouting and name calling on a daily basis. And then a challenge arose from the middle management folk, sensible people, who formed a counter group that called itself the League of Professional Educators: LOPE. Their members were loyal to Dr. Ammerman and their professional status, and they wanted to do absolutely nothing to change things.

The discussions, the arguing, the hostilities, the misunderstandings, etc., took up the entire fall semester of 1969. By December in this mess I was unsure of what would happen in general and specifically to me. I was an innocent, even though nobody believed that. Would I be fired? Was my teaching career at an end? I was warned by unsympathetic people that this would be the case. Was the newly formed Faculty Association doomed to extinction? As the semester drew to a close, it was all up in the air. Now this is where a little gesture can alter a situation in unforeseen ways. There was this official form that somehow came into my possession—a piece of paper, among so much junk that we and LOPE and everyone else generated from mimeograph machines. I filled it out—on what I believed was on my way out—and sent it to the county labor something. As I saw it, it contained a hopeful sentiment: that it might be nice to have a faculty union at the college. As it turned out, it was a formidable document. Within weeks, word came down that we had to have a vote—yes or no—for the establishment of an officially recognized bargaining unit. So we all voted, and the union won, by about a 65% margin. Many were surprised, including myself. New York State had recently passed a pretty decent Taylor Law. And all you had to do was fill out a piece of paper which by law required an institutional vote for or against a faculty union. A curious footnote to this law was that anyone going around promoting the formation of a union could not be fired without the administration suffering consequences. Without realizing, I had led a charmed life because I was just such a nuisance. But we had a contract. Even so, faculty relations with the administration and the county were pretty bumpy for long while, until Ellen Shuler Mauk became president, and things began pretty much to cool down. In fact, the very nature of the contract, once understood by both sides, had a normalizing effect on these relations.

We did in the late 1970s come close to having a strike. I was no longer president, Jack Schanfeld was, but I was still active and I thought a strike would prove a milestone in faculty power as well as bring us up to the salary scale in Nassau Community College, which was then 20% above ours. A strike, by my calculation, wouldn’t last a week. As negotiations stalled and the strike campaign went forward, passions rose. We had a big meeting in the Shea Theatre, the whole faculty showed up and a lot of shouting took place, and a vote was needed. Right then. But how? We were all just standing and sitting there. So I had the terrific inspiration, which was to count the votes by dividing the constituency, pro and con, into two halves of the theater’s seating. It would be a moment of truth. The separation took place. With large numbers on either side. The motion to strike was defeated by a slim majority. But the visual effect of the separation was horrible, full of tension. The faculty had separated visibly, and now teachers looked across the theater at each other with real animosity. And in one remarkable instance, the separation occurred between a husband and wife, one voting for and the other against a strike. I can’t imagine what dinner was like for them that night. But this was a bad move. What I learned is that you don’t lead by creating hostile divisions. The existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre in his one-act play No Exit has a character claim, famously, that hell is other people. My feeling is just the reverse. It’s other people who make life worthwhile—interesting, amusing, and expansive—especially in friendship with people who have an academic but also adventurous view of the world. They are life-enhancing, even when there occur serious disagreements among them. Fortunately our differences over the strike vote were soon healed, even though now and then, as I walked through the Southampton Building, I might hear some sociology teacher comment to an office mate: “There’s that Eriksson again”—i.e., causing trouble. And at one dramatic moment an art teacher caught sight of me at the other end of the hall and started shouting—there were classes going on in every classroom, “Eriksson, I will never go on strike! Do you hear me?”—everyone heard him—"I will never go on strike!” Did he really hate me? I laughed. He was only letting off some steam. Somehow we still became friends. Some twenty years later he actually supported me as a playwright. His attitude, as he came to see it, was that we were all in the same game together.

History is a living, breathing phenomenon. It’s not something to be simply recollected or accounted. It’s a lived experience within another time and space. It defines us and we continue to learn from it. We have much to learn from our past as we continue to build the future because Ed is right: we really are all in the same game together.

|